The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has classified Delta as a “variant of concern” circulating in the U.S., which means it may carry a risk of more severe illness and transmissibility.

It accounts for about 10 percent of the country’s COVID-19 cases.

Estimates vary, but Ben Neuman, virologist at Texas A&M University, said the Delta variant is

“considerably” more transmissible than the Alpha variant, which was the contagious strain first

detected in the U.K. that quickly became the dominant variant. Alpha, at that time, was considered

more transmissible than regular non-variants. As the different variants continued to compete against

each other throughout the pandemic, Delta has pushed out the others as the more dominant strain.

“These viruses are fighting for our lungs, and this appears to be one that has an advantage over other strains of SARS-CoV-2,” he said.

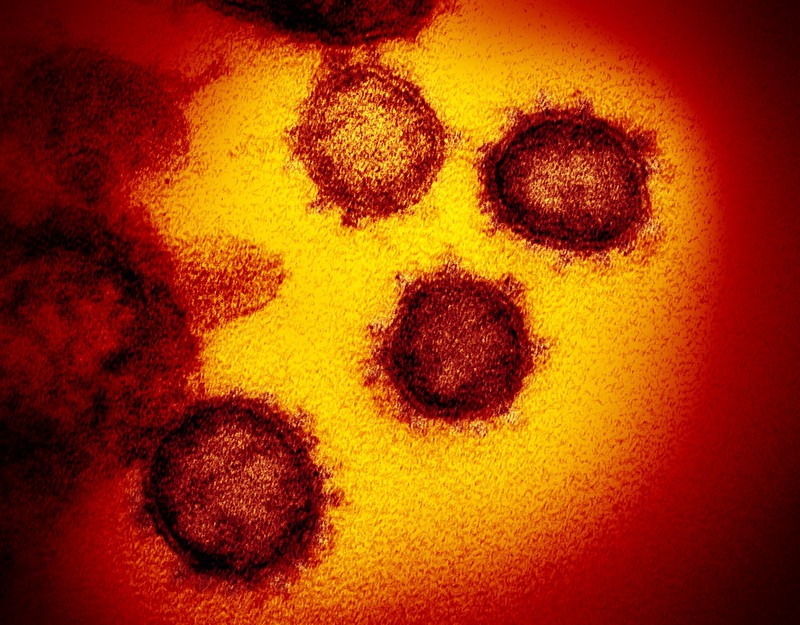

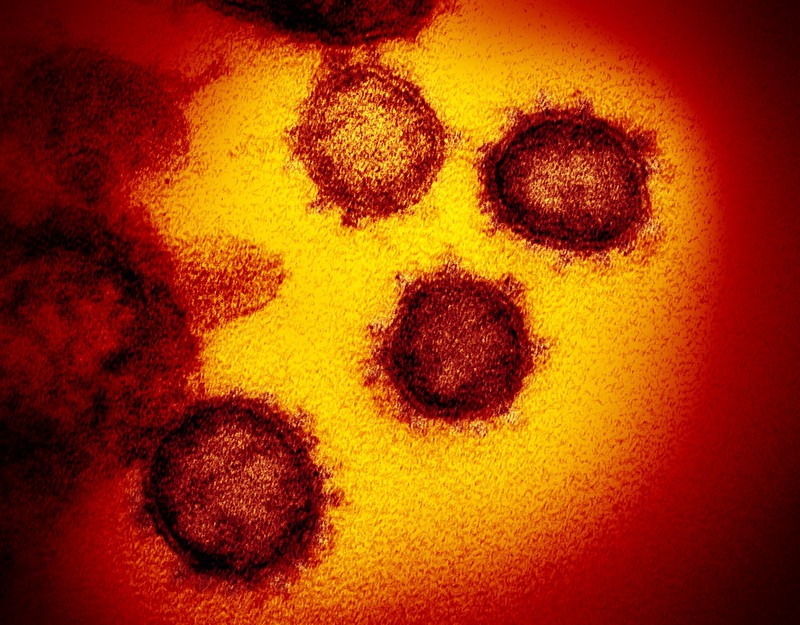

Neuman explains that viruses must change in order to survive. One virus can turn into around

100 million inside an infected person over the course of a day. He said viruses are also sloppy

in that they’ll make a random mistake in about one of every three copies it makes – and in

some instances, those mutations can give the virus an advantage over other versions.

“Mutation is how the virus responds to the world. It’s basically how they are able to stay in the

game, how they’re able to stay competitive,” he said. “That’s all they are. They’re just

competitive little things that make mistakes in order to adapt or respond to their environment.”

In the Delta variant, the mutation is a change in position in its spike protein, which allows the

virus to penetrate and infect healthy cells. Neuman said a similar variant circulating in Texas

and Mexico has the same mutation.

Though a strain may have advantages over others, Neuman said its spread often comes down

to the activity of people. Two people standing 20 feet away from each other probably won’t

transmit the virus, regardless of the variant. But if an individual is in close contact with

someone who’s infected, they’re likely to be exposed and likely will catch that variant if they

don’t have immunity.

“Our vaccination rates are not high enough to where we can expect that this virus will go away

on its own,” Neuman said.

---------------------------------

More severe and more contagious

The Delta variant is much more contagious than the other

variants identified so far.

“It is about 2.6 times more infectious than the original strain,”

said David Fisman, epidemiologist and professor at the

University of Toronto.

“This means it will cause larger epidemics and be more difficult to

control.”

“We find that patients with the Delta strain are three

times more likely to go to intensive care and twice as likely to

die than patients with the original strain of SARS-CoV-2,”

he added.

The Delta variant has several mutations in the S protein on the surface of the virus, one of which seems to make it more transmissible.

Limited data from China suggest that the viral load of Delta infections can be up to

1,000 times that of the original strain, Fisman said. “People also seem to become

contagious more quickly with the Delta strain,” he added.

This variant, first identified in India, currently exists in 124 countries,

13 more than last week. In comparison, the Alpha variant, first identified in the

United Kingdom, is present in 180 countries (six more than last week); the Beta variant, first identified in South Africa,

is in 130 countries (an increase of seven); and the

Gamma variant, first identified in Brazil, has reached three more

countries this week, for a total of 78.

Criticism of the variant detection protocol

Experts and doctors are concerned that Quebec is underestimating the presence of

the Delta variant in the province. Most establishments are not allowed to carry out

screening and sequencing of cases themselves, so when COVID-19 patients are

admitted to hospital, health-care workers are often unaware of the strain they are

dealing with.

While this does not change the work of staff in the health network, it does raise

concerns among specialists and in certain establishments, who would like to be able

to screen the cases themselves.

“We don’t know, but we don’t need to know, because it is the same precautions, the

same treatments and the same support,” said François Marquis, head of the

intensive care unit at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital.

According to him, Quebec has seen low case numbers from the Delta variant

“because the borders are closed and because we are mostly vaccinated,” adding that fully vaccinated people seem relatively well protected against severe illness and death related to the variant.

But some experts say the screening should be carried out by the health centres

themselves. “Most have been banned from screening or sequencing variants in their

labs and must send their samples to the provincial public health lab (LSPQ).

I wonder if this method is reliable, and if we really are at five per cent,“

said Roxane Borgès Da Silva, professor at the Université de Montréal’s school of

public health (ESPUM).

“Outside of major urban centres, I know there are several regional microbiologists

who would like to be able to do the screenings and who, at the moment, are not

allowed to,” she added.

Like others, Borgès Da Silva believes it is essential to give health establishments the

necessary tools to screen cases before the possible increase in Delta variant cases.

“There is no reason why, at some point, this strain won’t become dominant, like in

many countries. There is a risk, as with the other variants, of getting there one day.

We must prepare for it,” she said.

Tracking progress

Hugues Loemba, family physician, virologist and professor at the University of

Ottawa’s faculty of medicine, agrees, adding that it is necessary to

screen and sequence as many cases as possible.

“It is important to monitor the progress of the different variants, because it would

allow us to put more stringent measurements in the regions where the presence of

the Delta variant is greater,” he said.

Loemba added that the Delta variant can cause large outbreaks and infect entire

regions. “We would not have to put the public health restrictions back in place in all

of Quebec, but we could set them in the regions most affected, to limit the spread of

the variant,” he said.

Ultimately, the goal is not to stop the spread of the variant altogether, but to slow

its progression, to allow time for the population to be adequately vaccinated,

he said. “We are not an island. We’re going to have a Delta variant wave for sure,

but it’s going to come later than in other countries.” He added that the Alpha variant

also caused a wave of cases in the United Kingdom and in Europe before arriving in

Canada a few months ago.

“The Delta is sure to become dominant. It’s written in the stars. The only reason this

wouldn’t be the case is either because we vaccinated everyone, or a new variant

arrives and takes the place of the Delta,“ Marquis said.

The symptoms of a COVID-19 infection from the Delta variant do not appear to be

the same as those from the initial strain of the virus. Loss of smell no longer seems

to be one of the main symptoms. The symptoms are more like the flu, Marquis said.

“Right now, in the northern hemisphere, there isn’t influenza, so if anyone has

flu-like symptoms, it’s COVID-19,” he said.

Sequencing and screening, what’s the difference?

Sequencing is the most efficient method of identifying variants, as it allows the

analysis of the complete genetics of a virus. However, it is a long and expensive

procedure that can only be done with a fraction of COVID-19 cases. Screening is a

faster, low-cost technique to determine if positive cases are due to any of the

variants. If a screening test is positive, health authorities may perform full

sequencing to determine precisely which variant it is.

– In collaboration with Pierre-André Normandin, La Presse,

and Agence France-Presse